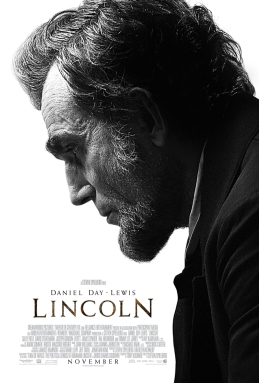

The recent Lincoln biopic by Steven Spielberg, with its masterful performance by Daniel Day-Lewis in the title role, has raised to a new level interest in the process whereby slaves achieved freedom during the Civil War. The film focuses on the events of January 1865, when Republican efforts led to passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution formally abolishing slavery throughout the United States. In the film Lincoln is anxious to get this passed as soon as possible, fearing that his 1863 Emancipation Proclamation might be overturned in the courts and convinced that the war would be concluded within the next month or two. Should members from southern states be readmitted to Congress he is rightly concerned that the body will not pass the amendment. Accordingly, Lincoln presses for passage of the amendment before the end of January, ensuring that freedmen could not be re-enslaved.

The recent Lincoln biopic by Steven Spielberg, with its masterful performance by Daniel Day-Lewis in the title role, has raised to a new level interest in the process whereby slaves achieved freedom during the Civil War. The film focuses on the events of January 1865, when Republican efforts led to passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution formally abolishing slavery throughout the United States. In the film Lincoln is anxious to get this passed as soon as possible, fearing that his 1863 Emancipation Proclamation might be overturned in the courts and convinced that the war would be concluded within the next month or two. Should members from southern states be readmitted to Congress he is rightly concerned that the body will not pass the amendment. Accordingly, Lincoln presses for passage of the amendment before the end of January, ensuring that freedmen could not be re-enslaved.

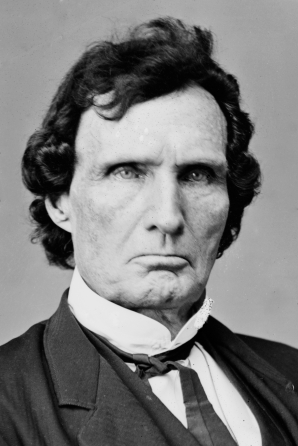

The unfolding of this drama is mesmerizing, and although we all know how it ends there are numerous twists and turns in the process of getting to the 13th amendment’s passage. One of the highlights of the film is Thaddeus Stevens, played by Tommy Lee Jones, returning home from Congress after the successful vote, taking the original document to show there. I won’t go any further with this description since it is one of the truly stellar moments of the film.

What I wanted to comment on, however, was not the film but the interpretation over time of the interplay between Lincoln, the various factions of Republican party, and the remaining Democrats in Congress in seeking racial justice. There has been considerable debate over the years of how best to situate Lincoln and his efforts on behalf of emancipation. There is no question that Lincoln and all members of the Republican party of the 1850s and 1860s opposed slavery and sought its end. The aggressiveness of that abolition, the method to be undertaken, whether or not slave owners would be compensated or not, and a host of other tactical issues might yield different positions but all Republicans opposed slavery.

At some level, it might be appropriate to conclude that Abraham Lincoln was essentially a moderate in this arena. In spite of his very real personal antipathy toward slavery, Lincoln moderated in his public statements because he could not afford to compromise his questionable popular base of support as president. As Lincoln wrote to newspaper editor Horace Greeley on August 22, 1862:

As to the policy I “seem to be pursuing” as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt. I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery.

Lincoln recognized that his administration’s ability to hold the nation together in the wake of southern secession was dependent upon his walking a narrow path of acceptability to a coalition of factions with sometimes divergent beliefs upon the slavery issue, that without enough support his position as president would be undermined and he would never be able to accomplish anything worthwhile. In spite of personal desires, it was a question for Lincoln of first things first.

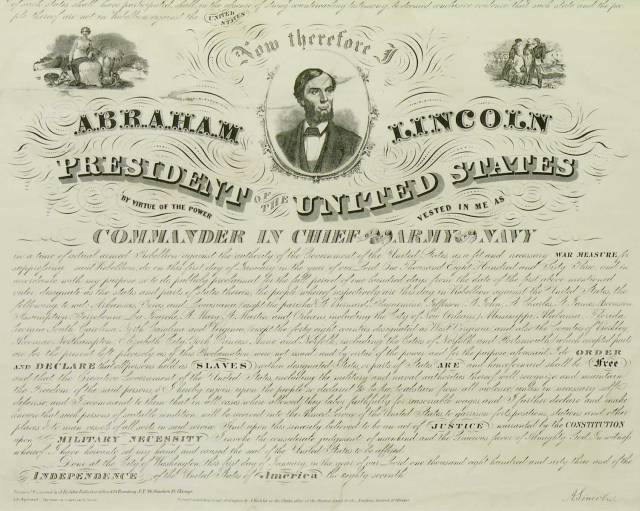

At the same time, within a few short months Lincoln had taken action to end slavery as a war measure. As he said in his Second Annual Message to Congress on December 1, 1862: “Without slavery the rebellion could never have existed; without slavery it could not continue.” His decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation was at least in part a response to this situation.

For many interpreters, Lincoln was essentially a pragmatist. He moved when the time was “right” and not before. We might celebrate this caution or condemn it, depending on our perspective. Lincoln’s hesitancy placed him at odds with radicals in Congress, led by Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, who argued for a ruthless prosecution of the war and a punishment of the South for its rebellion. They established a Committee on the Conduct of the War that pressed Lincoln daily about the aggressive prosecution of the war and punishment of the South.

The radicals were committed to the immediate ending of slavery, and to make it an early war aim. Thaddeus Stevens stated the case for the war as being prosecuted to end slavery in January 1862: “The occasion is forced upon us, and the invitation presented to strike the chains from four million of human beings,…to extinguish slavery on this whole continent; to wipe out, so far as we are concerned, the most hateful and infernal blot that has ever disgraced the escutcheon of man; to write a page in the history of the world whose brightness shall eclipse all the records of heroes and of sages.”

Lincoln refused to take such an aggressive and controversial approach. Not until nearly two years into the war did he issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which transformed the Civil War from an effort to preserve the union into a moral crusade to end slavery in the United States. This played into a larger national narrative about the United States being founded on a set of moral precepts in which all are created equal that had been somehow subverted through slavery. One might appropriately ask, how much less vigorous might the Union army have been had it not become the instrument of abolition and the quest for racial justice?

But was Lincoln really a moderate, or more of a radical than he has traditionally been given credit for? I like the book by Hans L. Trefousse, The Radical Republicans (Alfred A. Knopf, 1969), which argues that the radicals, with whom Lincoln jousted throughout the war were really Lincoln’s vanguard for racial justice. They served as lightning rods for the antislavery agenda that Lincoln and all members of his party sought. Having been elected to Congress from districts supportive of their aggressive abolitionism, the radicals served as “blocking backs” for Lincoln and made it possible for him to move out on the ending of slavery more readily than he would have been able to do otherwise; indeed by the fall of 1862 the path toward emancipation was clear.

This is an interpretation that is more in keeping with recent trends in the historiography of the Civil War. Based on Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, this film is quite reflective of the interpretation of Lincoln as far-thinking political strategist who mobilized the radical wing of his party to achieve his end of emancipation for all slaves for all time. We don’t see a lot of divergence over objectives by Lincoln and the radicals in Congress in this film, only over tactics and timing.

What do you think? How should we interpret the ending of slavery in the United States? This new Steven Spielberg film give us an opportunity to reconsider the place of Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the 13th Amendment in the nation’s history.

I am very conflicted over this issue. I have long been a fan of the early abolitionists, but regret that they transitioned from peaceful non-resistance advocates to believing that only bloodshed would free the Slaves. Their cause was just, but the truth is that we as Americans are still fighting the Civil War. War was not the solution to what divided us as a nation. I am currently working on a monograph about Edward Everett and the preserving of Mount Vernon. I long derided Everett for being a “Cotton Whig,” but am more and more coming to see the value in what he attempted to do in the run up to the Civil War in trying to preserve the Union through peaceful means. Everett appealed to Northerners and Southerners alike to not break up the Union based on fidelity to the memory of their forefathers (and especially George Washington) who had sacrificed so much to bring the 13 diverse colonies together into a Union of States. Edward Everett wanted to end Slavery, but his primary concern was to preserve the Union. He gave a speech on “the Character of Washington” 129 times all over the United States over a five year period before the eve of the Civil War to raise money to first purchase then preserve Mount Vernon, but also the message he presented was an appeal for preserving the Union. While the speech was very well received, even in the South, it was sadly not powerful enough to stem the tide of war…a war that is unfortunately still being fought today.

LikeLike

….Sorry Roger, but as compelling as Spielberg’s “Lincoln” is, I’m still convinced that Turtledove hit the nail on the head in “Guns of the South” as to what the Emancipation Proclamation was: a weapon to turn a socioeconomic dispute into a crusade whose goal was more focused towards punishing the Confederacy as a whole for secession, with emancipation of the slave labor forces being – as my history mentor at Texas U, Dr. Brown once put it – “more of a fortuitous happenstance of crippling the South’s total manual labor pool by liberating the enslaved portion of said labor poo; than a honest, honorable goal of putting an immediate end to the evils of human bondage in this country.” Considering it took a full century before Black Americans finally received their full rights as citizens of this nation with the Civil Rights Acts during the LBJ administration, and especially taking into account just how much long-term damage the ineffective and more destructive Reconstruction was with regards to integration, it’s pretty clear that as far as the Union was concerned, Slavery was first an excuse for war, then a sword to wield in a crusade, only to get tossed aside to fend for itself rather than take the Biblical advice and beat swords on all three sides into plowshares that would, as one, properly rebuild the States into one true Union.

Still, damn good movie, with the only real concern being whether or not Lewis may have permanently damaged his health by getting *un*fit for the role…:(

:OM:

LikeLike

Good comment. I will agree that the Emancipation Proclamation was a war measure, Lincoln said so repeatedly throughout the rest of his life and even states that in the film where he explains that the 13th Amendment was necessary to ensure that emancipation was not overturned in the courts. I know that at least in part it was also designed to visit economic ruin on those in rebellion. I’m not willing to go quite so far as you that this was either the only reason or at least the most important reason for Lincoln’s taking this action. Eliminating slavery as a moral blight on America had been a fundamental precept of all Republicans since the formation of the party in the 1850s–Lincoln said as much many times–and the “twin relics of barbarism” statement condemning slavery and polygamy was ensconced in the Republican platform. Your comments on the failure of Reconstruction to ensure civil rights for the freed slaves are critical to any serious discussion of the Civil War, but unfortunately most American history surveys break at 1865 and they should probably break in 1877 at the earliest. Anyway, thanks much for your thoughts.

LikeLike

Nice article, I had never heard of Trefousse, but I will definetly chech out his book. I think that Lincoln may have been more in the “radical” camp than people give him credit for. The proclamation was not issued until September of 1862, however he made it known (at least to some cabinent members) that he wanted to make a move against slavery, months before and was persuaded to wait for a decisive Union victory. So, I can’t help but wonder how long before he even made it know had he made up his mind? Slavery was such major issue, he must have been thinking about abolishing slavery for quite a while even before he made his intentions known to his cabinent. We will never know how long he had been thinking about abolition or how long before he had decided to make an emancipation proclamation.

Additionally, I think that when studying the ending of slavery, the role of the slaves themselves is over looked. Runaway slaves flocked by the hundreds and thousands to take refuge behind union lines. This as a result created a huge refugee problem. In addition it raised the immediate question of: what should be done with these people? Should they be sent back to slavery? If they were to be sent back should it happen immediately or after the war ended? As a result of these questions the north needed a unified policy; the emancipation proclamation provided a broad guide to help answer these questions. In a sense the pressure created by the refugees helped push the issue of emancipation. The emancipation pelroclamation said that these people would no longer be slaves, and equally important, it also said that the North was going to arm and train black soldiers.

LikeLike

Glad that you found the post interesting. You are right about the slaves and their flocking to the Union lines. This prompted John Charles Fremont first, and then other Union commanders, to declare them in 1861 “war contraband” that was “confiscated” to create a legal status for them and ensure that they would not be returned to their owners. It was a brilliant ploy, both expedient and precedent setting, and it helped pave the way for more far-reaching and permanent decisions about the status of the slaves. Anyway, thanks for your comments.

LikeLike