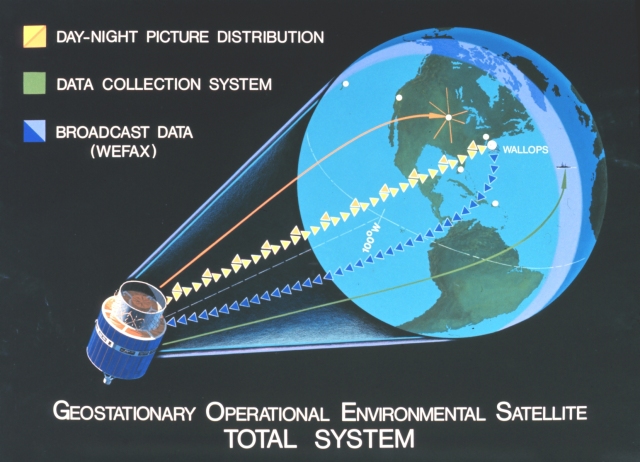

This graphic shows the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) Total System as developed in 1977.

I was recently asked this question, how do space activities contribute to our daily lives? I must confess that I have been asked it many times previously. Virtually every time this question is asked, however, it is because the person asking it usually is seeking a set of talking points supporting greater expenditures for space activities. Often that is manifested in a desire to articulate an expansive vision for human space exploration. Unfortunately, that is a difficult case to make. There are very real and important reasons to undertake space activities; but at least thus far very few of them require humans flying into space.

Space-based assets are critical to many aspects of modern life on Earth. Satellites in Earth orbit are also critical to supporting the infrastructure of all manner of activities on Earth, including virtually every aspect of global telecommunications. There is also a significant scientific return from space activities.

The returns on investment in space, which are only now beginning to be realized, involve the geophysical inventory of a planet and the exploitation of regions beyond for all types of ventures that have changed our lives. Remote sensing satellites have made life strikingly different from what it was as little as a generation ago as satellite images of weather patterns enable meteorologists to forecast storms, as communications satellites have transformed our ability to move information, and as global positioning satellites are starting to provide instantaneous reliable geographical information.

I want also to say something about the so-called “spinoff” argument. Much has been made over the years of what NASA calls “spinoffs,” commercial products that had at least some of their origins as a result of spaceflight-related research. Most years the agency puts out a book describing some of the most spectacular, and they range from laser angioplasty to body imaging for medical diagnostics to imaging and data analysis technology. NASA has spent a lot of time and trouble trying to track these benefits of the space program in an effort to justify its existence, and the NASA History Office has more than five linear feet of documentation relative to the subject. With the caveat that technology transfer is an exceptionally complex subject that is almost impossible to track properly, these various studies show much about the prospect of technological lagniappe from the U.S. effort to fly in space.

Whether good or bad, no amount of cost-benefit analysis, which the spinoff argument essentially makes, can sustain NASA’s historic level of funding. Spinoffs, by definition, are unintended consequences of another activity. They might be highly useful and lucrative consequences, but they are nonetheless unintended. Trying to defend a program based on unintended consequences seems to me to be a poor argument.

More useful, I would assert is a counterfactual question. How would life today be different if there were no space program? There can be no fully satisfactory answer to that question. One person’s vision is another’s belly-laugh. But perhaps we can begin with the elimination of the microchip. Whether our life would be significantly different is problematic, but I think many of the high technology capabilities we enjoy—starting with biomedical diagnostics and related technologies and ending with telecommunications breakthroughs—might well have followed different courses and perhaps have lagged beyond their present breakneck pace as a result.

Some of us might well think that a positive development, though I doubt most would want to go back to typewriters, problematic global communication, etc. The point, of course, is that the past did not have to develop in the way that it did, and that I believe there is evidence to suggest that the space program pushed technological development in certain paths that might have not been followed otherwise, both for good and ill.

While the proponents of spaceflight might celebrate “spinoffs” of technology as emblematic of “good things” accruing to those civilizations that undertake spaceflight, there is one major outgrowth of spaceflight that cannot be denied, national security space operations. This is certainly the case with the United States and the national defense apparatus could not function without surveillance, communications, weather, early warning, and navigation satellites, to name just a few.

Most important of all, especially during the Cold War but also during and since the 1990s, the technology of spaceflight made possible something never envisioned before in human history, the capability to undertake surveillance on all manner of actors—including state, non-state, individuals, ethnic or racial groups, and organizations. Even before the launch of Sputnik in October 1957 both the United States and the Soviet Union realized the potential offered by reconnaissance and other types of overhead surveillance.

At the same time a little-known principal critical to the safety of the entire world also resulted from Sputnik. The Soviet satellite established the overwhelmingly critical principal of overflight in space, the ability to send reconnaissance and other satellites over a foreign nation for any non-lethal purpose free from the fear of attack on them. Orbiting reconnaissance satellites served more than virtually any other technology as a stabilizing influence in the Cold War. The ability to see what rivals were doing helped to ensure that national leaders on both sides did not make decisions based on faulty intelligence.

Both the Americans and the Soviets benefited from this new reconnaissance satellite capability, and the world was at least marginally safer as a result, but it might have turned out another way. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson did not overestimate the importance of this technology in 1967 when he said that the U.S. probably spent between $35 and $40 billion on it, but “If nothing else had come of it except the knowledge we’ve gained from space photography, it would be worth 10 times what the whole program has cost.”

Satellites for commercial, national security, and scientific purposes are enormously significant reasons for undertaking space activities and have restructured American society since the 1950s. The one area that has not fundamentally reshaped society is human spaceflight. That is not to say this will not have a major impact into the future, but in so many ways the human part of the U.S. space program is the least compelling of any aspect of space operations. I’d like to see that change. We’ll see. I welcome anyone’s thoughts on this issue. What am I missing?

While it may be the hardest to justify on a cost/benefit analysis, humans in space are an inspiration to many youths who then seek education in maths and sciences because of this – a definable benefit to society. And I believe that the manned flights to the moon were the most important undertaking of the 20th century – not only in science or engineering, but philosphically in leaving the Earth. Manned spaceflight also inspires people to dream and imagine bold undertakings, and I think we’d be much poorer without such dreams.

LikeLike

Roger, you are absolutely right. I have been involved in everyprogram from the first Atlas, Corona, satellites through the Apollo Program. I agree that the most benefits we have gained is from the various satellites we launched. Very little was gained from the Apollo or shuttle programs in terms of advancing the benefits that were gained in the satellite programs at a much lowere cost.

The only thing the Apollo and Shuttle Program proved was we had the technical know how to build and launch a very expensive piece of hardware.Sure going to the moon was great, but what did we learn. That it was just a cold barren place with no way to sustain life. But it did provide millions of dollars worth of advertising for NASA.

The rocket launching tonight has been the largest contributor to man’s knowledge of the heavens of any system yet developed. Every launch was designed with specific goals in mind and the returns continue years after a launch.

What we have gained without the benefit of manned launches has been phenominal showing we don’t need manned missions to explore the upper atmosphere to get a nice return on our space dollars.

It has been a good pardnership between NASA, USAF and the civilian participants on unmanned flights with a positive return on our investment, Too bad NASA did not invest the trillians of dollars wasted on Apollo and the shuttle program on further space exploration satellites.

I may get flak on my comments but I was there and saw the waste on Apollo. I also saw what they were doing on the fiasko called Shuttle.

Again, you are so riight and should be commended for telling it like it is.

LikeLike

In terms of tangible results, whether scientific or practical applications, human spaceflight has provided the lowest bang for the buck of any space expenditure. But man does not live by bread (or bytes of data) alone, and the inspiration provided by human spaceflight has had tremendous impact. I don’t think that it’s merely coincidence that the decline of the American human spaceflight program so closely correlates with the decline of the United States itself.

LikeLike

Human spaceflight has provided more information on the Moon than most think. The lunar samples collected and experiments left on the surface have given us a good deal of data, including new information about the history of the Moon AND the Earth.

Also, a human spaceflight program to Mars would be more beneficial than any robotic mission ever flown. It’s important to remember that Mars has all the ingredients for life (it was once warm and wet) and generally speaking where this is water, there is life. The problem is that you could send thousands of probes to a planet like Mars and never find any fossils or signs of life. It takes trained scientists, archaeologists, and paleontologists to find these type of things, not robots controlled remotely by humans 30 million miles away while dealing with a 17-minute delay in signal/command reception.

Think of the impact both technologically and philosophically if we were to find life on another planet. Think of the possibilities that might exist elsewhere in the universe. Think of the opportunities it would open up and the inspiration it would provide here on Earth. By figuring out what wiped out most life on Mars, we could figure out how to protect our own planet.

LikeLike

I want to dispute the assumption that without the space program, there would be no integrated circuits.

First of all, the first major program win for ICs wasn’t in NASA, it was in the Minuteman II guidance computer. You might object that ICBMs go through space, but this was a nuclear delivery program, and would have existed regardless of whether the space program proper had been started.

But beyond that, there was demand for ICs right down here on Earth. The Navy, for example, was having serious problems with the reliablity of avionics. if I recall correctly, at one point 1/4 of all carrier based planes were out of service at any time due to avionics malfunctions. The lack of reliability was due to the large number of soldered interconnections. Electronics faced a reliability wall unless these interconnections could be reduced. And that’s what ICs do: they move almost all the connection between components onto the chips, where they are made in a few deposition steps and are vastly more reliable. The chips are also smaller, lighter, and use less power, but those desirable attributes are secondary to that of a system that works at all.

LikeLike

During Apollo I believe NASA (North American) was using 80% of the IC’s available in this country. That may have contributed to development, even if the chips themselves were not invented by or for NASA.

LikeLike

NASA eventually authorized the construction of 75 Apollo Guidance Computers. The Minuteman II program, however, had 500 active missiles by May 1969, each with its own computer. The demand (and, importantly, the prospective demand after the program was committed to in 1963) dwarfed that of the Apollo program.

It’s quite reasonable, in my opinion, to say Apollo contributed to the development of ICs. It is not reasonable, however, to conclude Apollo was necessary for the development of ICs, or that ICs would not have come about, or even been seriously delayed, had Apollo not existed.

LikeLike

Thank you. Given the size of the Minuteman program I have to agree.

LikeLike

even before the Minuteman, we had computers on every Atlas site, using the old IBM cards to run a program. That was part of my job as senior Quality Control Rep to run verificaton tests on the cards before we used them.. As far as I know, every Atlas in off site bases and those at Vandenberg were all checked out by computer. I believe they were Burroughs Main Frame. We didn’t have the small ic cards but used relays, circuit boards, transisters and open faced telephone relays in a hundred cabinets in the lower air conditioned level to do the work. We used the same terminology of board placement that was later used on the smaller computers used in Apollo. The Titan also used the computers to check out intergrated systems and by the time of the Minuteman, we were well along with computer technology. What I saw on the Apollo Program was nothing like the systems used in the early missile checkout and launch.The first time I saw the computer used in factories was on the programmable controllers which incorporated small IC cards.

Having worked on both, I only saw a natural progression that led up to the personal computers in the eighties. To say that the Apollo Program developed the IC cards is stretching it a bit.

If the truth were Known, General Dynamics Convair came up with the requirements for a computer controlled system back in the early fifties. They knew that in order to launch an ICBM, it would take more that mere humans to track every device and system leading to a a launch. Along with developing a missile program, they also were pushing for a computer controlled system that woould launch a rocket with the push of a button. When one looks at the guidance packages used on the Atlas, one sees the beginning of micro circuits and devices, circuit boards and relay transister packages that evolved into the present day computer.

LikeLike